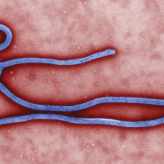

After weeks of discouraging news of the Ebola outbreak, the first reports of patients possibly fending off the disease have arrived: Two Americans, Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, aid workers who were in Liberia with Samaritan's Purse, received an experimental “secret serum” and have showed progress in their conditions, reported CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta.

But what exactly is the secret serum? It’s a question practically everyone’s been asking. The answer: Something the National Institutes of Health and Mapp, the biopharmaceutical firm that manufactured it, are largely keeping mum about. As far as we know, Gupta has the most details regarding the serum’s effect and what it does. As he put it in his CNN report:

The medicine is a three-mouse monoclonal antibody, meaning that mice were exposed to fragments of the Ebola virus and then the antibodies generated within the mice's blood were harvested to create the medicine. It works by preventing the virus from entering and infecting new cells.

In other words, the serum, named ZMapp, is a cocktail of antibodies, all proven to have effectively battled Ebola out of mice, that have been extracted for further testing. But before the serum got there,

the outbreak occurred, resulting in its use now. Even without FDA approval, Gupta writes, the serum may have been given under the Agency's "compassionate use" regulation, allowing it to be administered in a time of emergency.AP

The serum's use in the Americans’ case is simple enough to follow. In a statement to The Wire, the NIH outlined just how the Americans ended up receiving experimental treatment:

Samaritan’s Purse contacted CDC officials in Liberia to discuss the status of various experimental treatments that they had identified via a search from the literature. CDC officials referred them to an NIH scientist who was on the ground in West Africa assisting with outbreak response efforts and broadly familiar with the various experimental treatment candidates.

The scientist was able to informally answer some questions and referred them to appropriate company contacts to pursue their interest in obtaining experimental product. She was not officially representing NIH and NIH did not have an official role in procuring, transporting, approving, or administering the experimental products administered to the two U.S. patients.”

But, the statement concludes, the manufacturer Mapp is where the serum began.

That’s where the history of the serum gets a little murky. We know what happened to ZMapp, of course—three frozen vials of it reached Liberia on Thursday, July 31, thawed over the course of eight to 10 hours, and afterward entered through an IV into Brantly, whose condition recovered within an hour—but not much about the before, or what’s in it.

According to a report in August 2013, the company, which collaborated with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, tested the serum on monkeys. When administered to monkeys within 48 hours of infection, there was significant chance of survival. The results showed that all four monkeys that received the serum within 24 hours of infection survived, and two of four who received the serum within 48 hours did so.

The Mapp homepage.

But beyond that study, Mapp provides little information on its Ebola research—its website, for example, is sparse, including few news updates to their research. The serum appears to have evolved from evolved from research conducted by the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute in 2012 that showed a mix of various antibodies could stave off the Ebola virus.

So why ZMapp, of all the experimental solutions to Ebola, of which there are many? Perhaps it comes down to Mapp’s recent successes: The NIH included Mapp in its $28 million five-year grant awarded to five companies to research Ebola further in March. A press release dated July 15, 2014 revealed that Defyrus, a private life sciences biodefense company based in Canada, had partnered with Mapp's San Diego-based commercialization partner firm Leaf Biopharmaceutical Inc., to push the ZMapp serum's clinical development. And just last week, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency announced it awarded a contract to Mapp to continue development of the serum.

Still, fighting Ebola means a multi-pronged attack. While Mapp's method focuses on eradicating the disease after infection, the NIH has been working on preventing it in the first place. In the NIH's case, it’s working to promote development of antibodies within the subject, instead of injecting them from an outside source that survived Ebola.

NIH immunologist and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr. Anthony Fauci offered The Wire an explanation of how the vaccine would work:

The vaccine is used to prevent Ebola infection... Studies in monkeys are encouraging in that when you vaccinate the monkeys, they make antibodies that protect them from deliberate challenge with Ebola.

If the vaccine proves safe and induces the response that we are looking for, then we will expand the trials and hopefully produce enough to start vaccinating health care workers who put themselves at risk by caring for Ebola patients.

In fact, the vaccine will start human testing in September, and if all goes well, will begin phase 1 trials in January 2015.

Even so, as Dr. Stephen Morse, professor of epidemiology at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, told ABC News, a vaccine would not fully eradicate the virus.

"It will provide another tool at least," he said. "You can try to contain [Ebola] by immunizing contacts and other people... That's essentially the strategy, [a vaccine] would make it a lot easier for healthcare workers."

But ultimately, despite the serum's success, it’s only being used on the Americans, two victims who could be transported away from the outbreak. The rest of West Africa remains in a dire situation: TheWHO puts the latest estimate at 887 deaths and 1,603 cases. Without further testing and understanding of experimental solutions, doctors will continue to battle the outbreak using simply containment.

The serum, therefore, is a temporary solution: It isn't the end to Ebola, but it could be the beginning.

Follow The Wire's timeline to learn how the disease spread.

This article was originally published at http://www.thewire.com/global/2014/08/why-did-two-americans-get-a-secret-serum-to-fight-ebola/375517/

Facebook Comment Here

No comments:

Post a Comment

Finish Reading ? Make Your Comment Now..!